Current Topics

Contribution of the Satoyama Initiative to implementing the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework and developing Circulating and Ecological Economies

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which entered into force on 29 December 1993, will reach its 30th anniversary next year. As of 17 January 2022, the CBD has 196 parties. In 2010, the 10th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP10) to the CBD was held in Japan (Nagoya, Aichi Prefecture). With the participation of 179 parties as well as relevant international organisations and NGOs, a new strategic plan for biodiversity, including the Aichi Biodiversity Targets was adopted for the 2011-2020 period. The Aichi Targets included a total of 20 targets, one of which, Target 11 was that by 2020, at least 17% of terrestrial and inland water, and 10% of coastal and marine areas are conserved through protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs). OECM is defined as "a geographically defined area other than a Protected Area, which is governed and managed in ways that achieve positive and sustained long-term outcomes for the in situ conservation of biodiversity, with associated ecosystem functions and services and where applicable, cultural, spiritual, socio-economic, and other locally relevant values1." This article focuses on the contribution of the Satoyama Initiative to OECMs, and also shines a spotlight on the Initiative's potential to contribute to the development of "Regional Circulating and Ecological Economies (R-CEE)" aimed at the integrated enhancement of the environment, economy and society.

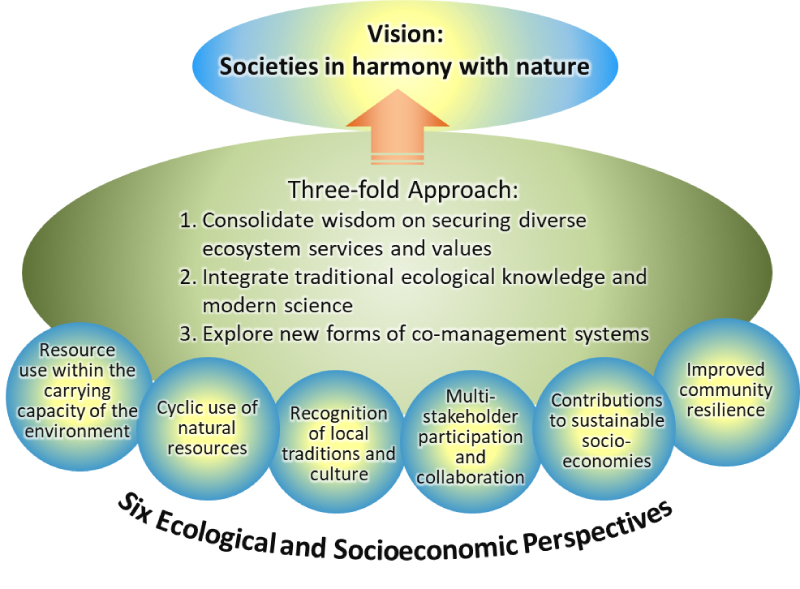

Amongst the various other debates and decisions of COP10 was the joint proposal of the "Satoyama Initiative" by the Ministry of the Environment of Japan and the United Nations University Institute of Advanced Studies (UNU-IAS, now the United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability). The Satoyama Initiative (Fig. 1) is a global effort to realize societies in harmony with nature based on a model of areas that are traditionally formed through the practice of sustainable agriculture, forestry and fisheries in Japan (called satoyama or satoumi in Japanese).2 While commonly referred to as satoyama, from a more scientific point of view, such areas where the interaction between people and the landscape maintains or enhances biodiversity while providing humans with the goods and services needed for their well-being are called Socio-ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes (SEPLS). Furthermore, to promote the work of the Initiative and knowledge sharing, the International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative (IPSI) was also established on the occasion of COP10. A total of 51 organisations joined IPSI as founding members, and as of February 2022, 283 organisations from 73 countries, including national and local government agencies, academic institutions, NGOs, indigenous or local community organisations, private sector organisations, the United Nations and other international organisations, have joined. To date, IPSI has carried out numerous related activities around the world3,4 (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Conceptual Diagram of the Satoyama Initiative

Figure 2. The Satoyama Initiative's satoyama conservation and restoration projects around the world (Top left: Restoration of locally-important plant species to enhance the sustainability of a SEPLS in Vietnam; Top right: Mangrove forest restoration aimed at improvement of SEPLS in Ghana; Bottom left: Biodiversity conservation planning activities aimed at adaptation to climate change in Bangladesh; Bottom right: Biodiversity conservation activities utilising indigenous knowledge in Panama) Source: SDM secretariat

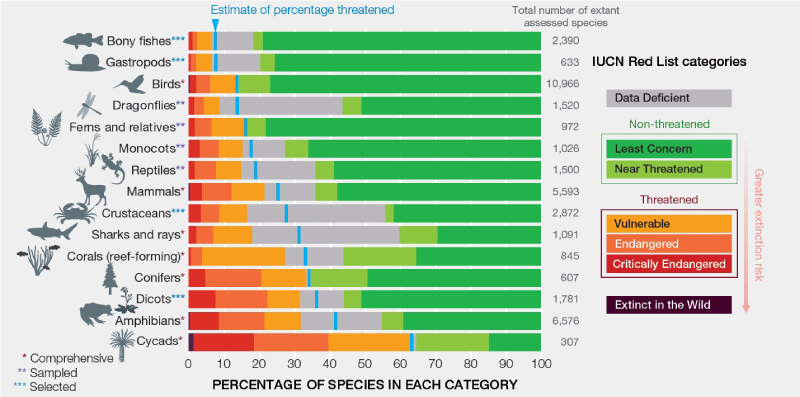

While efforts to conserve biodiversity have progressed globally since COP10, the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services published by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) in May 2019 asserts that biodiversity and ecosystem functions continue to rapidly decline. On average, about 25% of animal and plant species groups, or an estimated one million species, are threatened with extinction (Fig. 3), and many of these will become extinct in the next few decades if appropriate action is not taken. Direct drivers of nature degradation are noted to be changes in land and sea use, direct exploitation of organisms, climate change, pollution, and invasive alien species, while indirect drivers include demographic and socio-cultural factors, economic and technological factors, institutions and governance, as well as conflicts and epidemics. The report points out that societal values and behaviours are the fundamental factors influencing these drivers, and that transformative change across various sectors is needed to realise sustainable societies.5

Figure 3. Current global extinction risk in different species group

Source: IPBES (2019)

As the Aichi Targets reached their target year in 2020, the CBD Secretariat published an analysis of the progress made towards the targets in the Global Biodiversity Outlook 5 (GBO-5) in September of the same year. According to this report, none of the Aichi Targets was fully achieved, and only seven of the 60 elements that make up the 20 Targets had been achieved. Target 11 consists of six elements, of which two elements were included in those achieved: (1) 17% of terrestrial and inland water areas conserved, and (2) 10% of coastal and marine areas conserved. However, the other elements were shown to have made "progress" and therefore, not yet achieved: (3) areas of particular importance conserved; (4) protected areas are managed effectively and equitably; (5) protected areas are ecologically representative; and (6) protected areas are well connected and integrated.6

Against this backdrop, attention has turned to the next strategic plan and targets for the post-2020 period (the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework). This new framework was originally due to be adopted at the 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP15) to the Convention on Biological Diversity in Kunming, China in October 2020. However, following repeated postponements due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the conference is now to take place two parts, in October 2021 and the third quarter of 2022(tentative), with substantive negotiations expected to be conducted in the second part. Accordingly, the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework has not yet been finalised and discussions on its content are ongoing. The first draft of the new framework was released in July 2021, comprising 21 proposed targets as new goals. Of these, one of the most important targets is considered to be the conservation of at least 30% globally of land areas and of sea areas (the "30 by 30" target). The full text of this target is as follows:

Target 3. Ensure that at least 30 per cent globally of land areas and of sea areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and its contributions to people, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes.

This "30 by 30" target was endorsed by participating countries at the G7 Climate and Environment Ministers' Meeting in May 2021 and at the G7 Summit in June. Likewise, it was endorsed or encouraged by participating nations at the G20 Environment Ministers' Meeting in July 2021. However, there are also some concerns over the target. Human rights and environmental groups have raised their concerns over the societal implications of the target, noting that indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs) could be deprived of their living areas and livelihoods if the expansion of conservation areas is not carried out with due consideration. Policies that integrate IPLCs and traditional knowledge are essential in all countries, for positive conservation and socio-economic outcomes have been reported when local communities are involved in the management of conservation areas7. Turning back to the Aichi target 11, the numerical elements of area were achieved while those on biodiversity importance, effectiveness/equitability of the management, linkage and integration were not. Thus, the new targets must achieve not only numerical goals, but also meaningful conservation in multiple ways. In this context, the role of OECMs should be highlighted as they could contribute not only to the expansion of the area under conservation but also to other important elements. Japanese case studies have shown that expanding conservation areas to satoyama, farmlands and peri-urban areas, rather than limiting them to government-owned land, can significantly reduce the risk of species extinction and increase the connectivity of conservation areas8. The fact that those areas are often owned and managed by non-governmental entities such as IPLCs and private companies sheds light on the importance of them as the guardians of OECMs. In other words, in achieving the "30 by 30" target, OECMs have the potential to increase not only the area under conservation but also the quality of biodiversity conservation only if we can create cooperative relations with multiple stakeholders.

SEPLS that are the target of the Satoyama Initiative are expected to contribute to OECMs. SEPLS are defined as "dynamic mosaics of habitats and land and sea uses, where the harmonious interaction between people and nature helps maintain biodiversity and ecosystem services while sustainably supporting the livelihoods and well-being of humans".9,10 They are often located in or adjacent to protected areas, or between protected and urban areas. As the natural resources in SEPLS are used and managed in a sustainable manner, the people can enjoy a range of ecosystem services from nature contributing to: conserving biodiversity, expanding the area and enhancing the connectivity of conserved areas, promoting responsible use and enhanced management by businesses and local communities. Accordingly, areas recognised as SEPLS have a high potential to be identified as either protected areas or OECMs. Many examples of such areas already exist,2,3 and the contribution of the Satoyama Initiative in promoting the conservation and management of SEPLS is expected to increase in the future. Moreover, the importance of managed ecosystems such as SEPLS is mentioned in the information document of the two bodies of the Convention on Biological Diversity on Expert Input to the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework (CBD/WG2020/3/INF/11 and CBD/SBSTTA/24/INF/31).

As described in the 2021 report of a joint workshop by the IPCC and IPBES, recent years have seen a growing debate on the need to tackle both biodiversity loss and climate change simultaneously. Not only are both urgent issues that require rapid action, but there is also the potential for trade-offs that could exacerbate the situation of one or the other if focus is placed on only one of the issues (e.g. deforestation due to the installation of solar panels). Likewise, approaches that take both issues into account could generate synergies and co-benefits, allowing for more effective measures to be taken. The report also addressed the effectiveness of landscape and seascape approaches, which considers the linkages between the distribution and habitats of species and various climatic zones, such as forest, savannah, mountain and marine ecosystems, while proposing biodiversity conservation methods that classify areas by spatial perspectives, such as protected areas that prioritise nature, spaces shared by nature and people, and urban areas. In recent years, Nature-based Solutions (NbS) have also been included as effective means of both conserving biodiversity and mitigating and adapting to climate change while improving human well-being. These approaches are in line with SEPLS concept.

In this context, Japan is preparing a mechanism to count the diverse areas managed by local governments and companies as OECMs. The mechanism covers "areas where biodiversity is conserved based on private or local initiatives", and considers these areas being conserved by companies, individuals/groups, and local governments, regardless of their original purpose. Examples of such areas include not only satoyama, which are considered to be SEPLS, but also diverse areas such as: corporate forests, areas managed through national trust movement, nature sanctuary areas, biotopes, forests managed by shrines and temples, areas of cultural and historical value, green spaces within corporate premises, urban green spaces, forests managed with the purpose of conserving landscapes, forests for disaster risk reduction, and retarding basins. Japan is currently exploring a mechanism whereby the national government certifies areas that meet certain criteria for evaluation related to biodiversity conservation. This means that not only traditional satoyama or SEPLS, but also that more modern land uses could have a role to play as OECMs if they are used and managed sustainably bearing contribution to long-term in-situ biodiversity conservation.

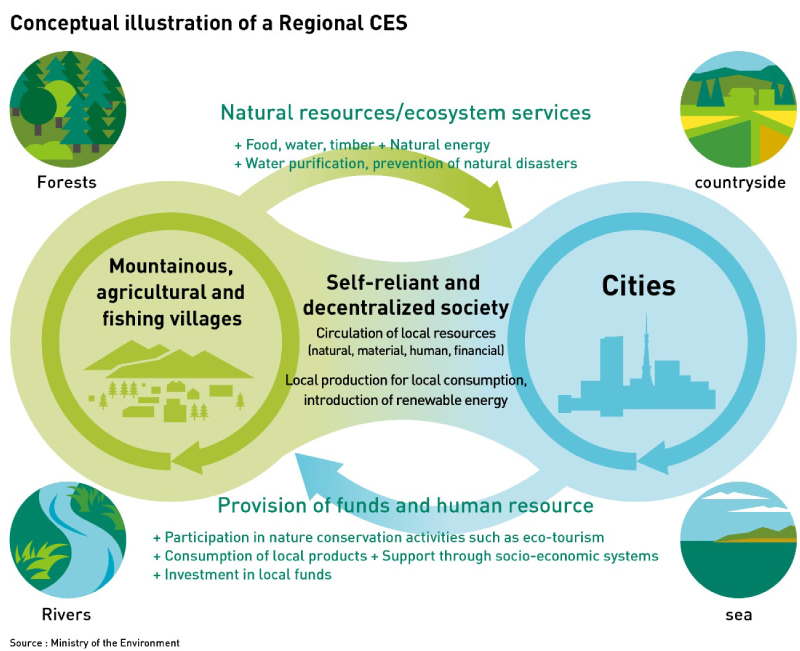

It is therefore hoped that SEPLS targeted by the Satoyama Initiative can contribute to the promotion of OECMs and the "30 by 30" target, which could become one of the key targets in the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. SEPLS also contribute to the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals 11 (especially Target 11.4), 14 (especially 14.5) and 15 (especially 15.1). In addition, properly conserved and managed SEPLS, which view the environment, society and economy as an integrated and sustainable system, are expected to contribute to Target 10 of the first draft of the new framework, which is to "ensure all areas under agriculture, aquaculture and forestry are managed sustainably, in particular through the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, increasing the productivity and resilience of these production systems." This is also linked to the establishment of Regional Circulating and Ecological Economies (R-CEE), which the Japanese government has included in its Fifth Basic Environment Plan. The R-CEE is "an approach that aims to maximise regional vitality by forming self-reliant and decentralised societies that make maximum use of local resources, such as beautiful natural scenery, while complementing and supporting other region's resources according to regional characteristics" (Fig. 4). R-CEE promotes sustainable and recycling-oriented societies and contribute to Sustainable Development Goals 8 (especially Target 8.4) and 12 (especially 12.2). SEPLS, OECMs and R-CEE are expected to play a part in synergistic development and transformative change going forward.

Figure 4. Conceptual illustration of Regional Circulation and Ecological Economies

- CBD. 2018. Decision Adopted by the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity 14/8 Protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures. https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-14/cop-14-dec-08-en.pdf

- The International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative (IPSI). The Satoyama Initiative. https://satoyama-initiative.org/concept/satoyama-initiative/

- IPSI. Case Studies. https://satoyama-initiative.org/case_study/#start

- Satoyama Development Mechanism. https://sdm.satoyama-initiative.org/projects/

- IPBES (2019): Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. E. S. Brondizio, J. Settele, S. Diaz, and H. T. Ngo (editors). IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany. 1148 pages. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3831673

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (2020) Global Biodiversity Outlook 5. Montreal.

- Oldekop, J. A., Holmes, G., Harris, W. E., & Evans, K. L. (2016). A global assessment of the social and conservation outcomes of protected areas. Conservation Biology, 30(1), 133-141. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12568

- T, Shirono., Y, Kubota., B, Kusumoto. 2021. Area-based conservation planning in Japan: The importance of OECMs in the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. Global Ecology and Conservation, Vol.30, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01783.

- IPSI Secretariat. 2015. IPSI Handbook: International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative (IPSI) Charter, Operational Guidelines, Strategy, Plan of Action 2013-2018. Tokyo, Japan: UNU-IAS.

- Nishi, M., Subramanian, S. M., Gupta, H., Yoshino, M., Takahashi, Y., Miwa, K., Takeda, T. (2021). Introduction. In Nishi, M. et al. (Eds.), Fostering Transformative Change for Sustainability in the Context of Socio-Ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes (SEPLS) (pp. 1-16). Springer, Singapore.